ART

WRITINGS

ABOUT

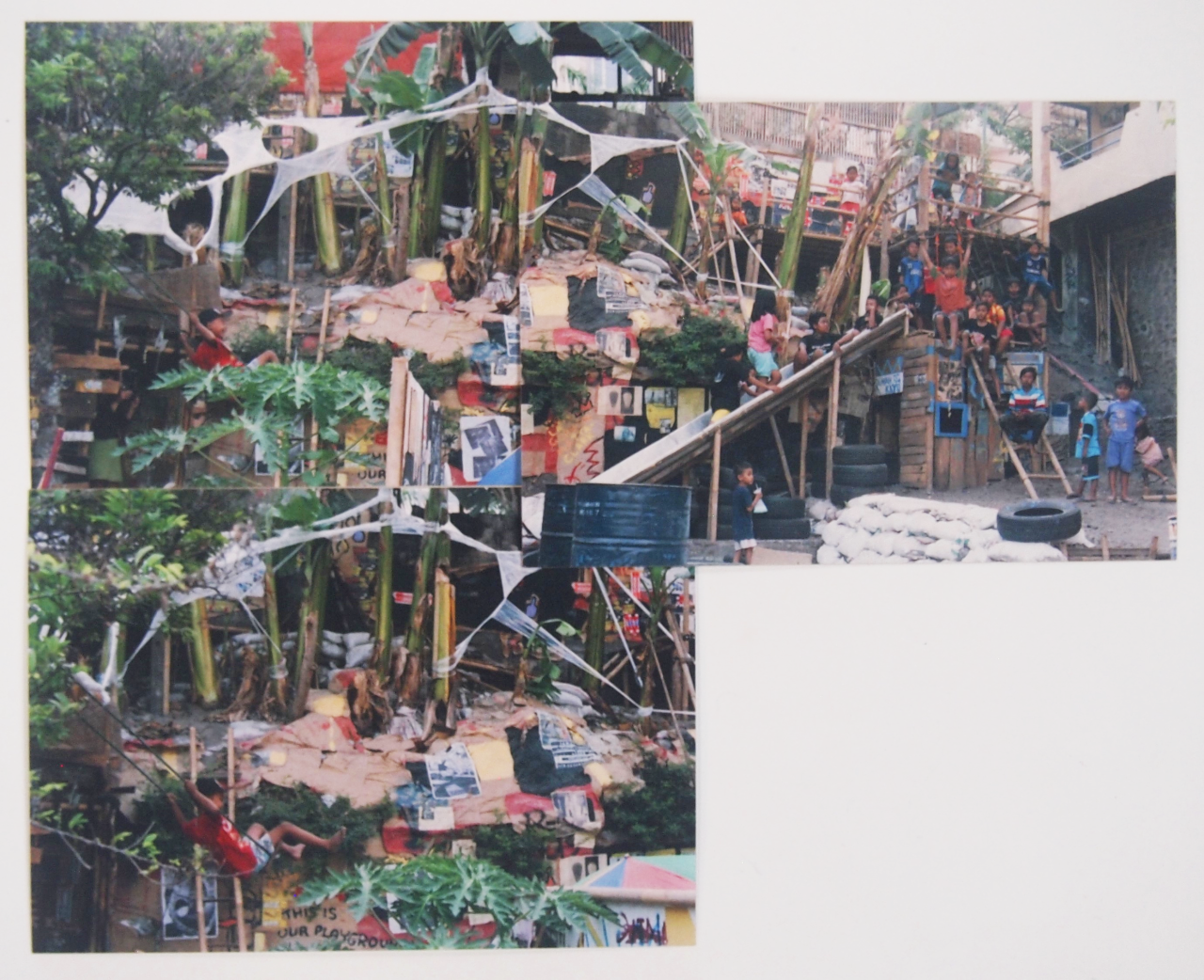

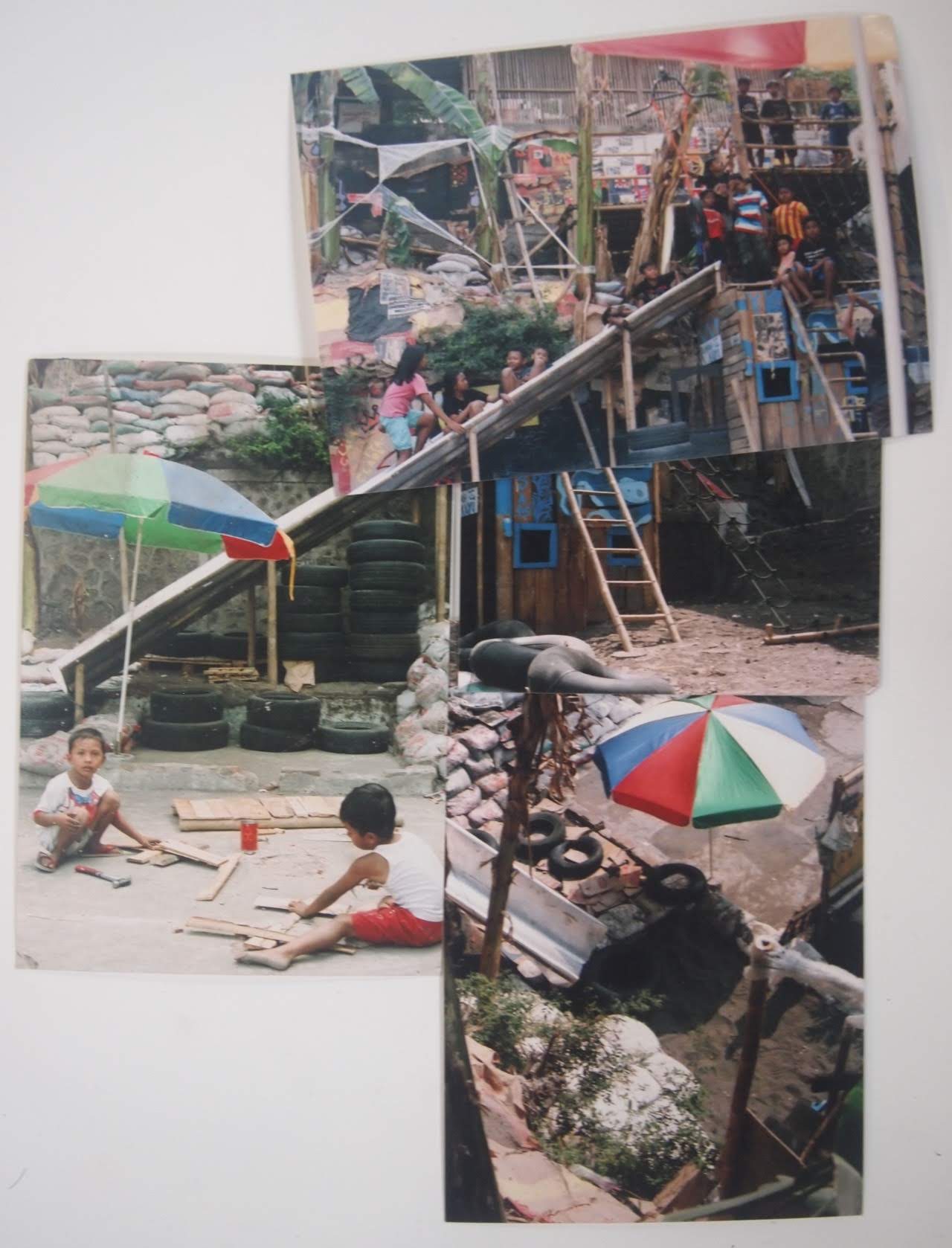

Alun Alun was a junk playground installation, built up over four months with children and other residents of Kampung Ratmakan, a neighbourhood on the banks of Kali Code, Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Inspired by the post WWII ‘junk playground’ movement in Europe, built by children themselves on bombed sites, the playground engaged children’s efforts to reach the world by testing out different configurations of ideas and materials. Through daily play with materials on the playground site, children were invited to implicitly critique and imaginatively reconfigure the relations and built form of their urban environment.

Childhood and youth are sites particularly affected by disruptions of social reproduction caused by global economic and cultural changes, and also sites of dynamic responses to such changes. Throughout the time of the playground project, childhood and youth were engaged as sites of an everyday politics of excess. Children’s disordering of space and intimate engagement with materials can productively accentuate the contradictions between the imaginary order of the world class city and the lived material realities of everyday life.

The playground was active for 5 months, in a gradual process of collaborative landscaping and construction.

Thanks to Rismilliana Wijayanti from Jogja Contemporary for facilitating our residency in Jogja, Kejilbergerak for support with translation and community liason, and of course the residents of Kampung Ratmakan for hosting, trusting and collaborating with us.

Within Kampung Ratmakan there are three adjacent pieces of land, running from the road to the river, which were sold 16 years ago to non-resident property speculators. The Kampung has temporary custody over this land until it is sold on, and are allowed to make use of it, but not to construct permanent buildings. The northern two blocks are usually referred to as the “lapangan” or field, and are where the playground is situated. At the time of our arrival this area contains a large concrete slab- used for events, informal futsal and badminton, several pigeon coops,a largely disused area which serves as a walking thoroughfare to steps leading the road and a steep bank composed of loose rubble, root systems, rubbish from the warungs (street eateries) above and banana palms.

Collecting materials involves interacting with Jogja’s all inclusive informal recycling economy, where all items of use value, from 44 gallon drums to plastic bags have a corresponding economic value, albeit one that is often up for negotiation. Most things can be found, sometimes through asking blindly and then following chains of interactions and recommendations, or by putting forward an offer for seemingly discarded materials put aside for potential later use

With sporadic help from kampung kids and youth, we begin by sandbagging the bank. In the process of digging up the soil and filling rice sacks, much rubbish is uncovered; glass bottles, endless drink sachets, leather bags, destroyed shoes, headless dolls, bottle tops, key chains, dog tags, toy cars, marbles. Four or five of the youngest and most curious playground regulars became active in this process, sifting through the rubbish and debris looking for any curiosities or things of worth. A broken watch is found and retained, a lipstick, a comb, a pink plastic bear, a pen, colourful plastic things that are no longer functional but retain an uncanny quality by the sheer fact of being there; weird stuff to find. These objects they refer to as ‘oleh-oleh’ (souvenirs), discarded objects retained as memorabilia from another place and time. Rizka is one child with a special tendency to take work such as these quasi-archaeological efforts very seriously. During the tunnel-digging, Rizka holds part of a house-brick in her hand and uses it to smash another object. “What’s that in your hand?” I ask. “It’s a hammer”, Rizka asserts. “No it’s not, it’s a brick”, one of the other children interjects. “No”, Rizka insists, “I’m using it as a hammer, so it’s a hammer”.

Materials collected and grown prepared, we begin an intense burst of building, working with handymen from the neighbourhood to construct some basic structures for kids to work off.

we copy kids, kids copy us, things are added and layered and rearranged, people make corners for themselves and the playground begins to develop a mood and an aesthetic...

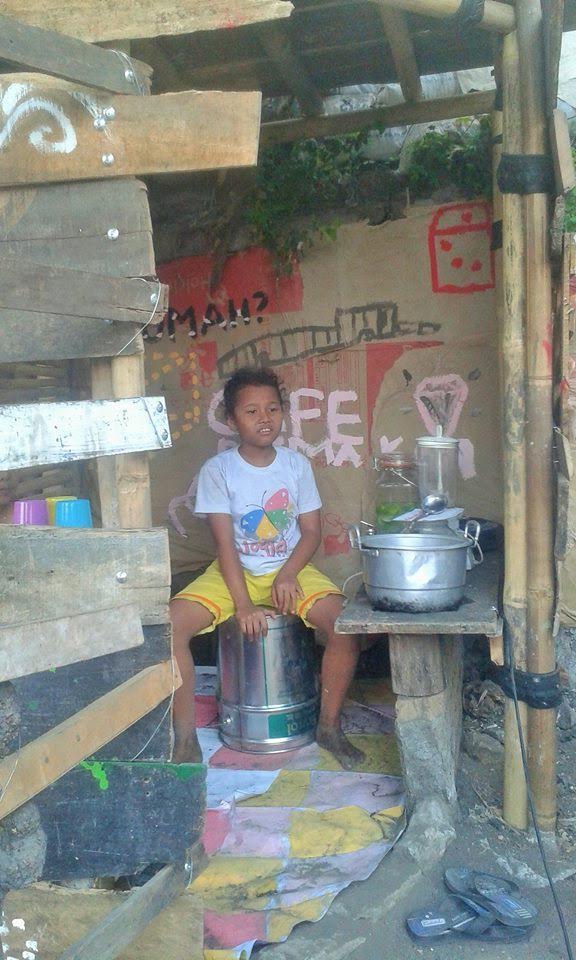

Five poles are concreted into the ground in a corner of the ‘ground level’ of the playground site. “What’s it for?” some children ask. “I don’t know, what do you think it should be for?” is Jorgen's consistent reply. Eventually Jorgen suggests to Elga, a 13-year old playground regular, that perhaps we could construct some sort of dwelling. The work is sporadic, as Elga quickly tires or becomes frustrated with the activity of hitting nails into flexible bamboo. Eventually the structure is built, including a dwelling below and a platform above, with a custard apple tree integrated into the structure, providing the vertical post for a ladder. The lower level is claimed by Elga’s 10 year old sister, Elva, who runs a café out of the dwelling on weekends. Elva accompanies Hannah to the nearby Beringharjo market where she is relentless in her haggling, shoplifting should she decide they are receiving ‘bule’ (foreigner) prices. Fruit and other ingredients are obtained. ‘Es Jeruk’, ‘Es Buah’, and ‘Es Kopyor’ are sold to children and other residents at a low price, competing with the drink stall operated by a mother at the opposite end of the lapangan. All earnings are scrupulously kept for the following trip to the market. Elga and his friends Arfa and Yanto claim the upstairs space of the structure, bringing a rug and some pillows. They like the exclusivity of the space, elevated directly above the activities of other playground users, and partly obscured under the leaves of the custard apple tree.

The Alun Alun Ratmakan Open day begins with workshops and an all in water/flour/paint fight organised by ourselves, followed by a series of children’s dance performances. From the fall of night onwards events are organised by the youth of the kampung, and much of what unfurls takes us by surprise. An impressive Chinese Dragon/Lion dance performance begins after sunset, an open mic style evening of stage performances is ushered in thereafter, followed by Dangdut karaoke, finished off with a Javanese drama written by local minor celebrity MC Donnie and performed by the kampung youth.

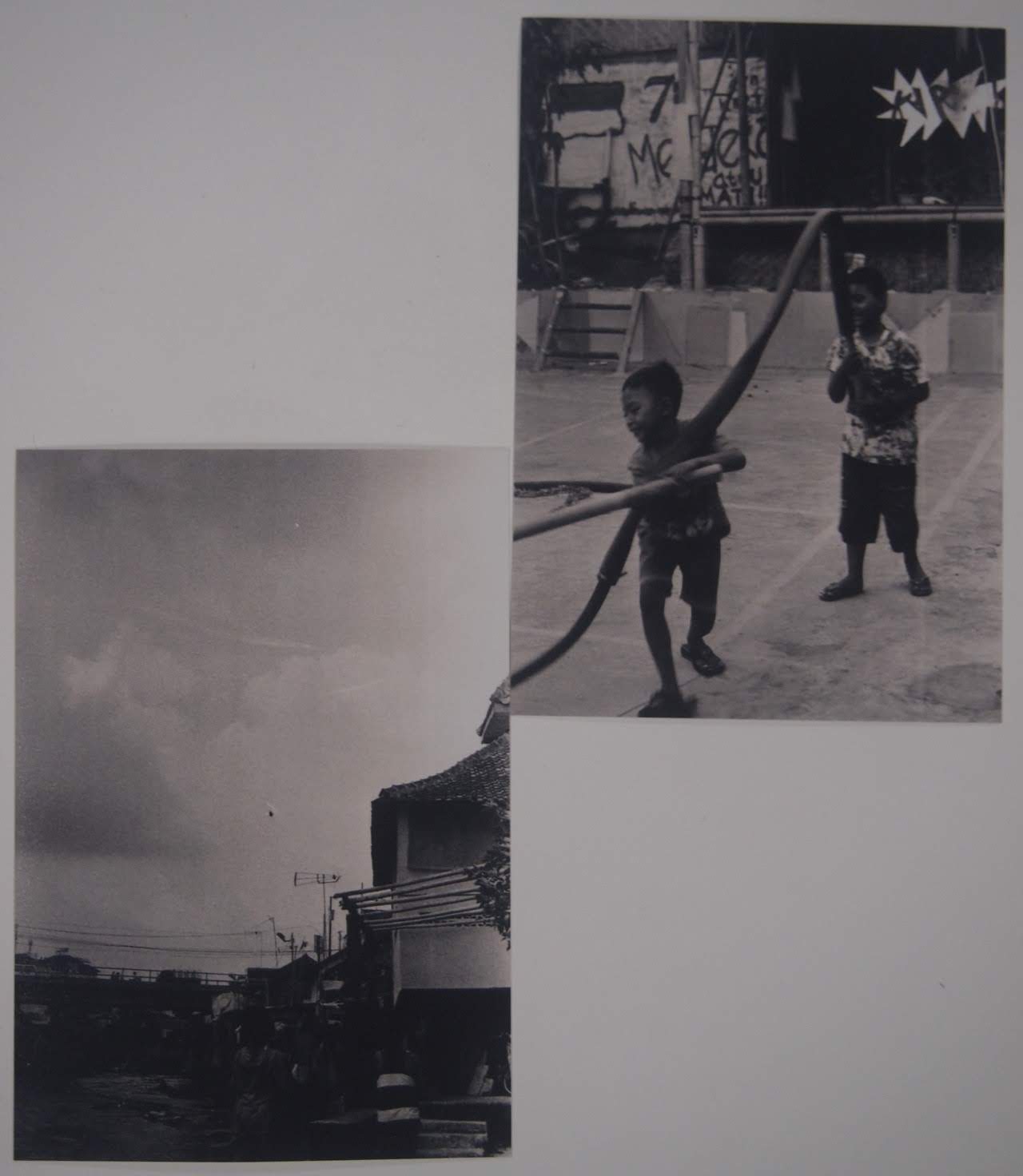

There is a large quantity of foam insulation for copper piping at the recycling shop above the playground. We purchase and deliver this to the playground site. The familiar question comes from the children – “What’s it for?” to which, of course, we answer that we don’t know and what do they think we should do with it. Through an elaborate synthesis of junk material, cultural signifiers, the everyday rhythms and movement of the kampung, Robby, an inventive young boy from the kampung, devises a use for the lengths of insulation and sets about cajoling other children to assist him. Lengths of foam insulation are tied together end-by-end to create a long snake-like body. Bamboo is fixed at right angles to the body of the creation, so that it takes five people to operate it. The creation is a barongsai (Chinese dragon puppet), which the children have seen a few weeks prior at the playground’s opening day festivities. Of course the dragon does not take on the quality of a mere imitation – because of the limitations of the materials used to make it, and the fact that it is always falling apart, the dragon becomes much more suffused with the personality traits of its maker, and his attempts to circumvent or accommodate the limitations of the materials. This dragon is first wielded on the concrete slab of the lapangan, but it soon becomes a means of navigating the immediate environment of the kampung. A procession of children, led by Robby and with the dragon raised above their heads, navigate the narrow alleyways of the kampung, coordinating their bodies, dodging other foot-traffic and turning sharp corners. The dragon, with its long, fluid body, allows the children to collectively perform their immediate environment as a metabolism; something a worm-like body could move through. It also facilitates Robby’s obsession with transport, serving as a vehicle for him to mobilise and cajole others into an activity he is convinced will be greater than its parts. Robby leads the other children into the apartment building neighbouring the playground, entering on the basement floor where some kampung residents live, following corridors then turning sharply up stairways, up to the ground floor where young migrant workers live. Down the corridors, a swift turn at a dead end, then up another flight of stairs to the top floor where foreigners and Indonesians on business stay. Robby disciplines those who fall out of rank or stall the dragon on the stairs. They take in all of the building and venture where they otherwise would not dare to venture.

Below is a diary, mostly visual, with a few notes of the playgrounds happenings over the 4 months it was active. for some more in depth thematic writings on this project see: